Workplace Harassment Explained

Now You Can Measure Workplace Toxicity. This Is Why It Matters.

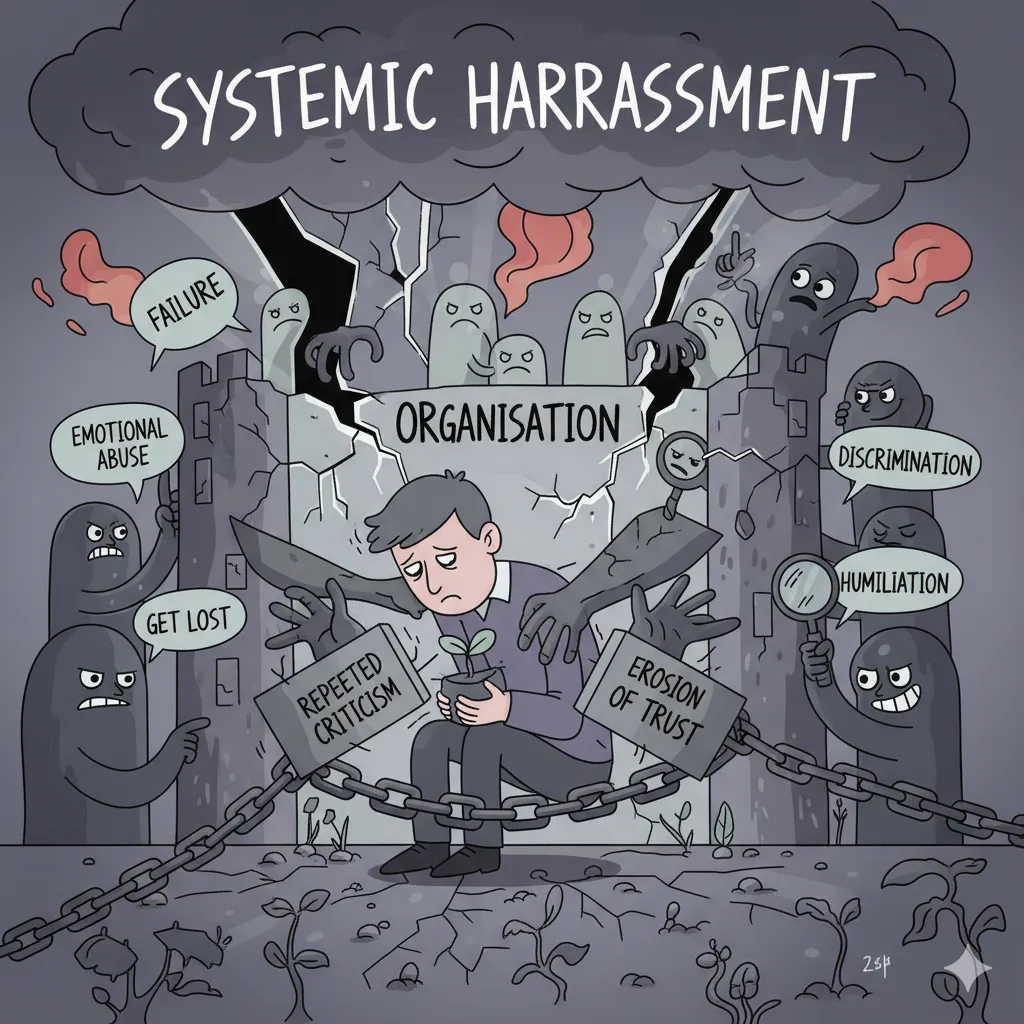

When discussing harassment, many see it as isolated events — like an inappropriate comment, a bad joke, or an overbearing boss. These actions are immediately noticeable. However, they often miss the underlying patterns: sarcasm that diminishes confidence, criticism that leads to isolation, threats that suppress, and discrimination that restricts opportunities.

Harassment is rarely a single event; it consists of a pattern of behaviours that undermine trust, hinder potential, and weaken organisations internally. Typically, people first think of sexual harassment, which is understandable given decades of workplace policies, training, and media coverage focusing on it, making it a prominent headline. However, the actual data shows that sexual harassment is often ranked lower in reports. The daily experience of harassment extends much further, including emotional abuse, repeated criticism, ostracism, humiliation, and discrimination. These are the behaviours most employees face, underestimated by managers, and not properly measured by organisations.

Harassment is rarely one incident. It is a system of behaviours that erodes trust, stifles potential, and weakens organisations from the inside. Left invisible, it creates workplaces where people show up but cannot thrive, where leaders lose credibility, and where safety and productivity are quietly compromised.

Formally defined, harassment is unwanted conduct which impairs dignity and creates a hostile or intimidating work environment for one or more employees. It takes many forms:

Physical harassment — assault, unwanted touching, or aggression.

Psychological harassment — bullying, intimidation, persistent humiliation, or mobbing.

Sexual harassment — unwelcome advances, coercion, or behaviour of a sexual nature that undermines dignity.

The impact goes beyond the office. Research confirms that unresolved harassment drives turnover, burnout, and absenteeism — with devastating effects on wellness:

Employees exposed to bullying are 58% more likely to take medically certified sick leave.

Chronic exposure to toxicity is linked to anxiety, PTSD, and even cardiovascular disease.

Harassment contributes directly to disengagement, knowledge loss, and avoidable costs that amount to billions of dollars globally each year.

The duty of the employer is clear: in line with the Code of Good Practice on the Prevention and Elimination of Harassment in the Workplace and the Violence and Harassment Convention, 2019 (ILO Convention 190), employers are obligated to manage and prevent harassment in the workplace.

These are not isolated acts. They are signals of deeper dysfunction — environments where unchecked behaviour corrodes wellbeing, fuels disengagement, and ultimately destabilises performance.

This report reveals underlying patterns, highlighting where harassment typically happens, who it affects most, and why it is important for workplace culture, performance, and sustainability. Although the focus is on mining, the message it conveys is universal: harassment is not solely about individuals, but also relates to workplace design and leadership accountability.

The importance of measurement cannot be overstated. For the first time, South Africa has established a national benchmark for harassment, with an average Harassment Risk Index (HRI) of 1.82. This figure is tangible and meaningful, representing the actual experiences of employees in diverse sectors. Some organisations demonstrate much better results, proving that safe and resilient workplaces are possible. Conversely, others have much higher scores, highlighting how harmful pockets of toxicity can weaken overall operations.

This goes beyond mere data; it tells a story of risk and resilience, turning numbers into meaningful insights. It invites us to view harassment not as a trivial concern but as a serious business risk with tangible consequences.

This report provides a summary of a study that was conducted in the mining environment. Get the full story about Workplace Toxicity HERE.

This report was independently prepared in accordance with the Harassment Risk Assessment (HRA) methodology. Its aim is to be informative and to enable readers to interpret and understand the HRA findings independently. The report was made possible through collaboration with Ms Josephine Petlele, whose MBA research, titled “The Relationship Between Harassment in the Workplace and Burnout Within the Mining Industry,” was supervised by Prof Renata Schoeman at Stellenbosch Business School. For information related to the academic research outcomes, Ms Petlele may be contacted directly.

Harassment Risk Assessment Dashboard

The dashboard provides an overview of harassment risk concentration across four classifications: Low Risk, Medium Risk, High Risk, and Extreme Risk.

A total of 207 participants took part in the assessment. The average risk index was 3.36 per participant, which is 86.6% higher than the South African market risk index of 1.8.

Explainer: The Harassment Risk Index (HRI) is calculated by dividing the total number of high and extreme harassment risks reported by participants, then averaging this across all employees. It provides a measure of how many serious risks the “average” employee encounters. The South African Market Index of 1.82 indicates that, nationally, workers face an average of just under two serious harassment risks.

This serves as a cultural benchmark for comparison: companies or industries scoring above it are more toxic than the national norm, while those below it are healthier.

With a score of 3.36, mining is not just above the benchmark — it is almost double the national level, placing it firmly in the danger zone for culture, compliance, and workforce wellbeing.

This means that, on average, each participant experiences nearly four harassment risks at an extreme or high intensity regularly.

One form of harassment can be damaging. But in mining, people face three or four risks simultaneously. This compounding effect intensifies stress, accelerates burnout, and pushes people out of the industry — often the very people companies most need to retain.

Harassment Types – Severity and Impact

The table below outlines the types of harassment with the greatest impact on your employees and the workplace.

The extreme and high risks are listed from highest to lowest in the table below. These risks should be regarded as lagging indicators, meaning they reflect risks that already exist within the business.

How do the top three harassment risks in South Africa compare to the Mining Study?

For the South African workforce, the most common harassment concerns are, on average:

Sarcasm

Discrimination

Humiliation

Explainer: These are not dramatic incidents. They are the “everyday” behaviours often dismissed as personality clashes or banter. Yet the data is clear: sarcasm, humiliation, and constant criticism are the most corrosive forces in the workplace. They undermine trust, create fear, and weaken performance far more than leaders may realise.

In the mining study, Threats rank as the top concern, compared to the South African average, where they are reported at a much lower level, in 11th position.

Comment: This shows a unique mining risk: direct intimidation. Threats do more than harm individuals. They silence entire teams, suppress reporting, and compromise safety culture — a dangerous liability in high-risk operational environments like mining.

How do the bottom three harassment risks in SA compare to the Mining Study?

Despite the broader context of gender-based violence and corruption, the South African workforce, on average, reports sexual harassment (unwanted touching and explicit images) and bribery among the bottom three concerns. Bribery ranks as the 12th highest concern in the mining study.

Comment: This challenges common assumptions. While gender-based violence dominates national headlines, the most toxic drivers inside workplaces are often different: sarcasm, discrimination, and intimidation. Companies have long embedded training on the Anti-Bribery Act and on sexual harassment (replaced in 2022 by the broader Code of Good Practice on the Prevention and Elimination of Harassment in the Workplace). The results show that these trainings, policies, and procedures have been effective—employees consciously limit their engagement in these forms of harassment because they know there will be consequences.

However, there is still a gap in managing other types of harassment. The key lesson is that if, despite South Africa’s wider societal challenges of gender-based violence and bribery, employees consistently report that these issues are relatively limited (though still present), then it is equally possible to reduce other types of harassment in the workplace through targeted management, training, and enforcement.

The risk index reflects the average number of high- or extreme-risk harassment experiences reported by participants. On average, each participant reported experiencing more than three of the 18 assessed risks at a high frequency and high impact level.

306 (8,21%) instances of Extreme risk

390 (10,47%) instances of High risk

480 (12,88%) instances of Medium risk

2,550 (68,44%) instances of Low risk

Note: medium risks should be viewed as lead indicators, and initiatives should be implemented to prevent these from escalating.

Breakdown in numbers

Breakdown in %

Comment: At first glance, the majority of cases fall into “low risk.” But this can be misleading. From a business perspective, the smaller cluster of extreme and high risks carries disproportionate weight. A single extreme case can spark lawsuits, reputational damage, or operational disruption. Research confirms that chronic exposure to workplace toxicity is linked to anxiety, PTSD, cardiovascular disease, higher absenteeism, and productivity loss. In short, even small pockets of extreme risk can destabilise the whole organisation.

The Harassment Risk Index represents the number of extreme and high risks that the average participant experiences. It provides a benchmark for comparison against the market: the lower the index, the more positive the outcome.

Note: For leaders, the HRI is not a statistic to file away. It is a governance dashboard. Just as safety incidents or financial irregularities are tracked and investigated, harassment risk must be treated as a leading indicator of cultural failure, talent flight, and ESG non-compliance. A rising HRI is a signal that leadership accountability is being tested — and that the cost of inaction will be paid in turnover, lost trust, and bottom-line damage.

In the mining study, Threats rank as the top concern, compared to the South African average, where they are reported at a much lower level, in 11th position.

Comment: This shows a unique mining risk: direct intimidation. Threats do more than harm individuals. They silence entire teams, suppress reporting, and compromise safety culture — a dangerous liability in high-risk operational environments like mining.

Key takeaway

The above establishes the foundation of this report:

Mining’s Harassment Risk Index (3.36) is nearly double the South African benchmark (1.82).

Employees face multiple overlapping risks, not isolated incidents.

Extreme risks, though fewer in number, are the costliest and most destabilising.

Everyday behaviours like sarcasm and humiliation are the true cultural toxins.

Threats and intimidation are uniquely severe in mining, threatening both culture and safety.

Sexual harassment and bribery although low, are not absent.

Note: This is not a “soft” issue. Harassment risk is as material to business performance as production figures or safety records. It is measurable, comparable, and actionable — and it tells leaders whether their culture is resilient or breaking.

Bonus Insights

The anonymous graph below indicates that the overall concentration of harassment risk in Extreme and High Risk exists in 33% of participants. (The table list to top concentration)

Average Harassment Risk Index:

Overall total respondents’ risk index:

696 Risks / 207 Participants = 3,36 risks per Participant

This is 86.6% higher than the South African market risk index of 1.8.

Note: This is not a marginal difference — it is an escalation. Mining employees face nearly double the risk burden of the national workforce. In benchmarking terms, the sector is not drifting slightly off course; it is heading into cultural crisis territory.

Pervasiveness of the risk:

69/207 = 33% of participants experienced high/extreme risk

138/207 = 67% of participants experienced NO extreme/high risk.

The Harassment Risk Index also reflects good news: in this instance, 7 out of 10 participants do not experience extreme or high risks.

Note: At first glance, this seems reassuring. But the other 3 in 10 are not just statistics. They represent whole teams or workgroups where harassment has become a daily reality. When a third of your workforce is at risk, it is no longer a series of individual problems — it is a systemic pattern that demands a structural response.

67% of participants experienced NO extreme or high risks. The extreme and high risks are concentrated in 3 out of 10 participants (33%). This is equal to the average South African pervasiveness.

Comment: This dual finding is critical: the overall spread (pervasiveness) mirrors the national picture, but the intensity inside mining is far worse. It is not about how many people are affected, but how much they are being harmed. Mining has the same breadth of problems, but the depth of damage is sharper and more severe.

Concentration Risk Index:

The Concentration Risk Index illustrates the distribution of harassment risks among participants, highlighting the intensity of risk concentration. It reflects the extent to which high-risk incidents are concentrated among respondents reporting risks.

696 risks / 69 Participants who reported Extreme or High risks = 10,1 per Participant.

It is concerning to note that the 3 out of 10 employees who experience extreme and high risks report, on average, nearly 10 different types of harassment regularly.

Explainer: This is what “concentration” really means. Those who are affected are not facing one hostile behaviour — they are living in an ecosystem of toxicity. Nearly 10 different types of harassment at once create environments of chronic stress, trauma, and disengagement. These employees are the ones most likely to exit, litigate, or collapse under the strain.

This shows that the participants who experience harassment risks are exposed to them at a very high intensity.

Explainer: The contrast between pervasiveness (how many are touched) and concentration (how much the affected suffer) matters. You can have a workplace where many people experience mild irritations — or one where fewer people face unbearable conditions. Mining falls into the latter category: fewer victims, but far greater suffering. From a leadership perspective, both are damaging, but concentrated suffering creates explosive hotspots of turnover, absenteeism, and reputational crises.

The more pervasive the concentration of extreme and high risks, the greater the effort required to address them. When these risks are not isolated to a small group but are experienced by the majority, they reflect a cultural behaviour embedded within the workplace.

Comment: This is the leadership alarm bell. When harassment becomes embedded, it is no longer about “a few bad actors.” It becomes a culture — sustained by silence, fear, and normalisation. That kind of culture doesn’t fix itself. It requires visible leadership accountability, targeted intervention, and a willingness to disrupt the status quo. Failing to act means allowing toxicity to harden into identity.

Key takeaway

3 in 10 employees are in high-intensity harassment zones — a third of the workforce in systemic risk.

The intensity of harassment in mining (10 risks per person) is far higher than national averages.

Pervasiveness may look “average,” but concentration exposes mining as a hotspot.

Those suffering face multiple, overlapping risks, not one-off incidents.

For leadership, this is a systemic culture issue, not an HR complaint log.

The above provides us with the texture: harassment in mining is not evenly distributed. It is concentrated, intense, and corrosive — a pattern that destabilises talent, performance, and culture at its core.

Gender Insights

Males and Females reported below the average risk of 3.63 at 2.45, and Males at 2.85.

Other, however, reported a dramatically higher risk index of 13.07.

The table below provides an overview of harassment concerns by gender group.

Comment: This single datapoint tells a powerful story. While men and women face harassment at manageable-but-serious levels, individuals identifying outside these categories face risks more than four times higher than the average participant — and nearly seven times the national benchmark. This reveals the extreme vulnerability of non-binary and minority gender identities in mining, where cultural recognition and safe reporting systems are almost absent.

Top Concerns by Gender Group

Males, Females and Other are concerned about different types of harassment.

Females rank the following as top concerns:

Sarcasm

Humiliation

Constant personal criticism

Comment: For women, the most damaging risks are not physical threats but daily indignities: sarcasm, humiliation, and relentless criticism. These are often dismissed as “just workplace banter” or “management style.” But when they become patterns, they erode confidence, isolate voices, and shut down contribution. The data shows that these “soft” behaviours are the most corrosive forces for women in mining.

Males rank the following as top concerns:

Threats

Discrimination

Constant personal criticism

Personal Circumstances

Comment: For men, the picture looks different. Threats and discrimination top the list, reflecting exposure to direct hostility, exclusion, or intimidation. Criticism and pressures tied to personal or family circumstances show how harassment can be used as a tool to undermine stability, reputation, and belonging. These findings show that men, too, face harassment with consequences for their safety, career, and wellbeing.

Other ranks the following as top concerns:

Violence

Threats

Personal Circumstances

Emotional Abuse

Knowledge and Understanding of Procedures

Sexual (Unwanted Material)

Comment: For employees who identify outside male or female categories, the risks escalate dramatically. Violence, emotional abuse, and sexual harassment are not just present — they dominate the list. These are the most severe forms of harassment, revealing that minority gender identities are treated as outsiders in mining workplaces, often subjected to open hostility and exclusion. This is more than a workplace issue; it reflects structural discrimination that leaves these employees with almost no safe ground.

Key takeaway

The above demonstrates that:

Gender differences in harassment are not just statistical quirks — they map to cultural patterns.

Women face subtle but corrosive daily hostility (sarcasm, humiliation).

Men face direct hostility and exclusion (threats, discrimination).

Non-binary employees face catastrophic risk, including violence and sexual harassment, pointing to systemic exclusion.

Harassment risk is not gender-neutral — it is shaped by identity, power, and belonging.

Comment: The lesson here is clear: harassment cannot be addressed with generic, one-size-fits-all policies. Leadership interventions must be tailored to the lived realities of different groups — recognising that vulnerability is patterned, predictable, and measurable.

Race Insights

Two race groups exceeded the average Harassment Risk Index (HIR) measured (3.36).

Indian participants reported the highest harassment risk index (4.53), while Coloured employees reported the second-highest risk index (3.6).

African and White participants reported a risk index below the average of 3.36. However, both are higher than the HRI for SA (1.82).

The table below provides an overview of harassment concerns by race group.

Comment: These numbers show that harassment risk is unevenly distributed across race groups. Indian and Coloured participants face significantly higher risks, pointing to vulnerabilities tied to minority representation and cultural positioning in mining workplaces. Harassment is not random — it follows the contours of identity and power.

Top Concerns by Race Group

Different racial groups are concerned about different types of harassment.

Indian participants’ top concerns:

Threats

Violence

Comment: For Indian employees, the highest risks are threats and violence — the most extreme forms of harassment. This suggests direct intimidation and hostility, exposing systemic prejudice and a dangerous tolerance for physical or coercive behaviours.

Coloured participants’ top concerns:

Humiliation

Sexual Harassment (Unwanted material)

Comment: Coloured employees highlight humiliation and sexual harassment as dominant risks. This mix reflects workplaces where employees are both publicly undermined and sexually targeted, creating a double burden of psychological and personal harm. It signals cultures of disrespect that strip both dignity and safety.

African participants’ top concerns:

Discrimination

Humiliation

Comment: For African employees, discrimination and humiliation dominate. This points to systemic bias in daily treatment — unequal access, marginalisation, and public shaming. Even if their overall risk index is lower, the persistence of these patterns shows structural inequality woven into the workplace fabric.

White participants’ top concerns:

Threats

Pressure to resign

Comment: White employees report risks that lean toward internal political manoeuvring: threats and pressure to resign. This suggests that harassment is used as a tool of organisational power play, rather than overt discrimination. It underscores how harassment adapts to context — targeting vulnerabilities differently depending on race and perceived power.

Key takeaway

The above reveals that:

Harassment is patterned by race, not equally shared.

Indian and Coloured employees carry the highest risks, showing heightened vulnerability for minority representation.

African employees face systemic discrimination and humiliation, reinforcing inequality.

White employees experience harassment through political pressure rather than cultural exclusion.

Harassment adapts to identity and context, exposing fault lines of representation, visibility, and structural bias.

Comment: For leaders, the message is clear: tackling harassment requires acknowledging how identity shapes risk. Without this, interventions risk being generic and ineffective, leaving the most vulnerable groups exposed to systemic harm.

Occupational Level Insights

Senior Management reported an above-average risk of 4.63, and Skilled Technical staff scored 3.97. The other occupational levels reported a risk lower than the average risk of 3.36. Only Occupational level 6 (Unskilled) reported a risk level lower than the South African Harassment Risk Index.

Legend to Occupational Code:

1 – Top Management

2 – Senior Management

3 – Professionally Qualified

4 – Skilled Technical

5 – Semi-Skilled

6 – Unskilled

Comment: This is a striking reversal of expectation. Many assume harassment is something that flows “top-down” from seniority to junior levels. However, the highest risk lies at the leadership and technical levels — those who hold visibility, accountability, and influence. This reveals that harassment in mining is not just abuse of power; it is entangled with responsibility, internal politics, and organisational stress.

Top Concerns by Occupational Level

Different occupational levels are concerned about different types of harassment.

Occupational level 2 (Senior Management) top concerns:

Discrimination

Constant Personal Criticism

Threats

Pressure to resign

Comment: Senior managers face harassment that undermines their credibility and threatens their career survival. Constant criticism, discrimination, and pressure to resign reflect cultures where leadership is undermined through political manoeuvring and hostile accountability. This corrodes trust at the top and fuels churn in leadership ranks.

Occupational level 4 (Skilled Technical) top concerns:

Humiliation

Threats

Constant Personal Criticism

Comment: Skilled technical staff — the backbone of operations — face humiliation and persistent threats. These specialists hold critical expertise, but harassment undermines their confidence and authority. The risk here is not only human harm but also operational fragility, as expertise is silenced or driven out.

Occupational level 3 (Professionally Qualified) top concerns:

Threats

Emotional abuse

Comment: Professionally qualified employees report harassment that targets their emotional safety. Threats combined with emotional abuse signal a culture that punishes competence, driving professionals toward disengagement or exit. This is talent erosion in action.

Key takeaways

The above shows us:

Harassment risk is highest in senior management and technical specialists — not just at the bottom.

For leaders, harassment manifests as political attacks and hostile accountability.

For technical staff, harassment manifests as public humiliation and intimidation.

For professionals, harassment manifests as emotional abuse that drives out talent.

Unskilled staff, surprisingly, report the lowest risk — highlighting that harassment is linked more to visibility and politics than to hierarchy alone.

Comment: This is a sobering insight, harassment in mining is not a trickle-down problem but a cultural design flaw. It targets those most visible, most responsible, and most essential to performance. Left unaddressed, it drives churn at the leadership level, weakens operational reliability, and strips out professional expertise — hollowing out the very capacities that make organisations sustainable.

This is the section that zooms out: it doesn’t just look at mining on its own but compares it against the wider South African workforce. The value here lies in showing how far out of line mining is, which groups are “hotspots,” and what that means for leadership, governance, and sustainability.

Benchmarking to the SA Market

The graph below provides an overview of how the data from the mining study benchmarks to the South African Market.

The Mining Study Harassment Risk Index (3.36) and the SA Market Harassment Risk Index (1.82) are used to identify outlier segments.

In addition to the average being significantly higher than the SA Market Harassment Risk Index, certain segments present a higher risk than the SA Market, posing threats such as talent loss, reduced productivity, impacts on employee wellness, reputational damage, and even safety incidents.

Comment: Benchmarking matters because it places mining in context. What looks “normal” within one industry may be a crisis when compared against the national baseline. Here, mining doesn’t just score higher — it overshoots dramatically, exposing cultural fractures that threaten its future sustainability.

Segments above the Mining Harassment Risk Index (3.36):

Other reported 13.07 — nearly four times the mining average, and seven times the SA market average.

Senior Management reported 4.63 — four times higher than the SA Senior Management benchmark of 1.04.

Indian employees reported 4.53 — three times higher than the SA benchmark for Indian participants.

Skilled Junior Management reported 3.97 — double the SA market equivalent.

Comment: These groups are the hotspots of harassment in the mining industry. Non-binary participants face catastrophic exposure — harassment as a constant state of being. Senior managers and skilled junior managers face pressure zones that undermine leadership and operational stability. Indian employees face levels of hostility far out of step with the rest of the workforce. Each hotspot signals talent flight, disengagement, and heightened legal and reputational risk.

Segments below the Mining average but still far above the SA Market benchmark (1.82):

Top Management reported 3.07, which is 16 times higher than top management in the SA market (0.19).

Professionally Qualified reported 3.14, almost double the risk of their SA counterparts (1.73).

Comment: These findings reveal that even when mining performs “better than its own average,” it still performs far worse than the national norm. This is like saying: “We are less bad than ourselves, but still crisis-level compared to everyone else.” It’s a sign that the baseline culture in mining is fundamentally misaligned with broader workplace standards.

Junior Segments:

The Unskilled segment reported a score of 1.33, which is lower than the SA Market Index of 1.87.

Comment: This anomaly flips assumptions. At the very bottom of the hierarchy, harassment is lower than average — likely because these workers have less visibility, fewer internal political connections, and fewer levers of influence. The real battles — and the real damage — are happening higher up the chain.

Key takeaways

The above makes it clear that:

Mining’s average harassment risk is nearly double the national workforce baseline.

Certain groups (Other, Senior Managers, Indian employees, Skilled Junior Managers) are outliers of extreme vulnerability.

Even “better” groups within mining (Top Management, Professionals) are still far above national norms.

The only group with a below-average risk is unskilled staff, showing that harassment risk is tied to visibility and internal politics.

Comment: The lesson here is that mining has normalised levels of harassment that would be considered a full-blown crisis in other industries. This is not about minor culture gaps — it is about an industry-wide tolerance for toxicity that erodes trust, undermines performance, and drives away talent.

The Story Behind the Data

When harassment is measured, it reveals what words alone cannot capture: patterns, inequities, and risks that cut to the heart of workplace culture.

The mining study makes one truth impossible to ignore — harassment is not an occasional lapse or the fault of a few bad actors. It is systemic, measurable, and consequential. It adapts to context, taking on different forms across various demographics, including gender, race, and occupational levels. For some, it appears as sarcasm or constant criticism; for others, as threats, humiliation, exclusion, or even violence.

The numbers indicate that harassment is not evenly distributed. While many employees may appear unaffected, those who are exposed face multiple, overlapping risks at high intensity. These are not mild irritations. They are chronic, corrosive experiences that erode mental health, silence voices, and destabilise teams.

The impact is not only personal — it is organisational. Talent is lost. Productivity falls. Safety is compromised. Reputations are damaged. The cost of harassment is evident not just in human suffering, but also in the bottom line.

Most tellingly, harassment is not “background noise” — it is a leading indicator. It signals where culture is breaking down, where governance is weak, and where leadership accountability is being tested. If ignored, it will harden into identity, shaping the organisation into a place where toxicity feels normal and resilience is impossible.

However, by making harassment visible — by measuring it, benchmarking it, and confronting its reality — leaders have the opportunity to take action. They can move beyond compliance to accountability, beyond silence to visibility, beyond risk to resilience.

This report is not just about mining. It is about the future of work, and whether organisations will choose to see harassment for what it truly is: a systemic risk that can and must be changed.